Latest news

3D illustrations of British History: Mary Stuart and Elizabeth I

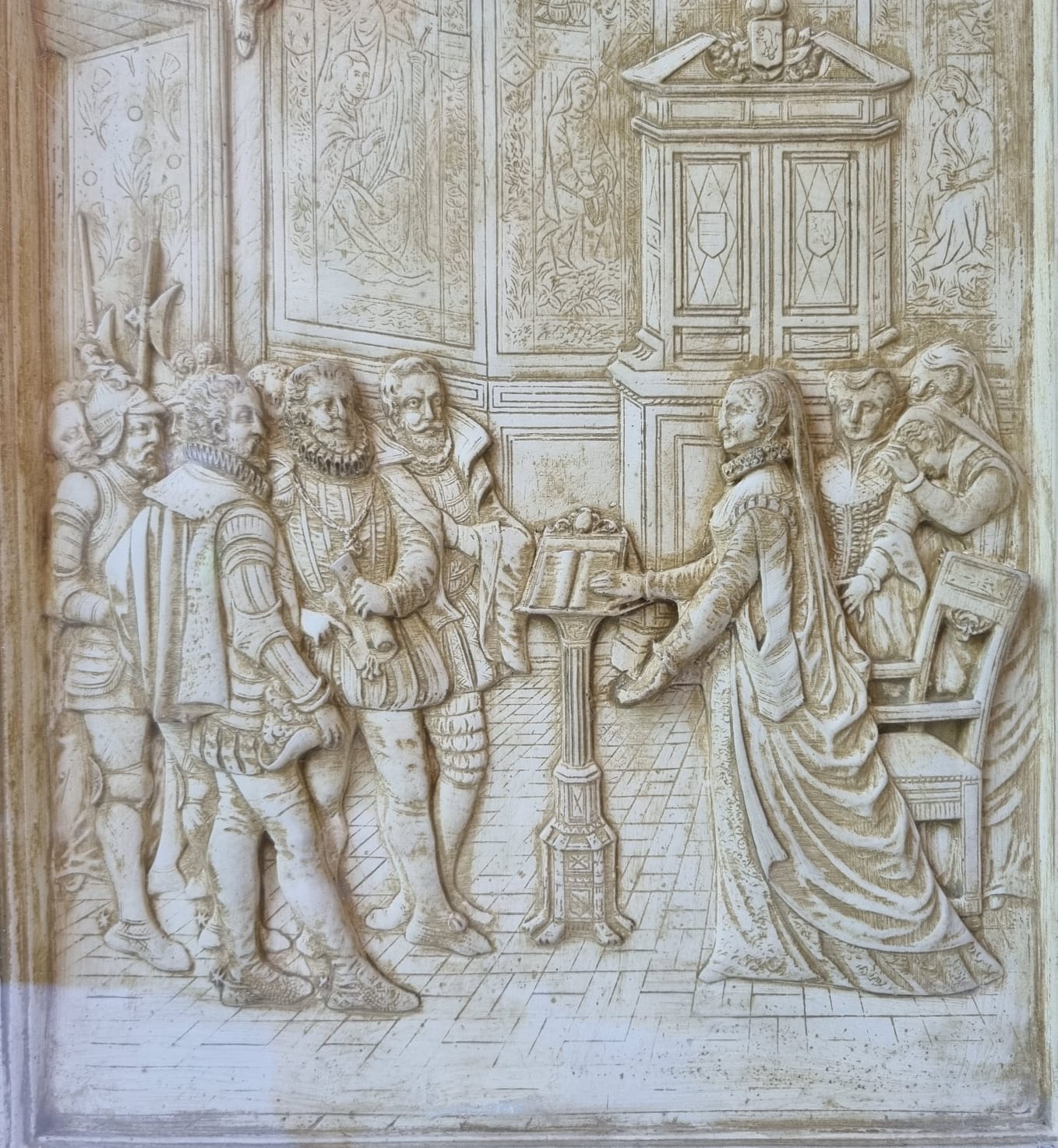

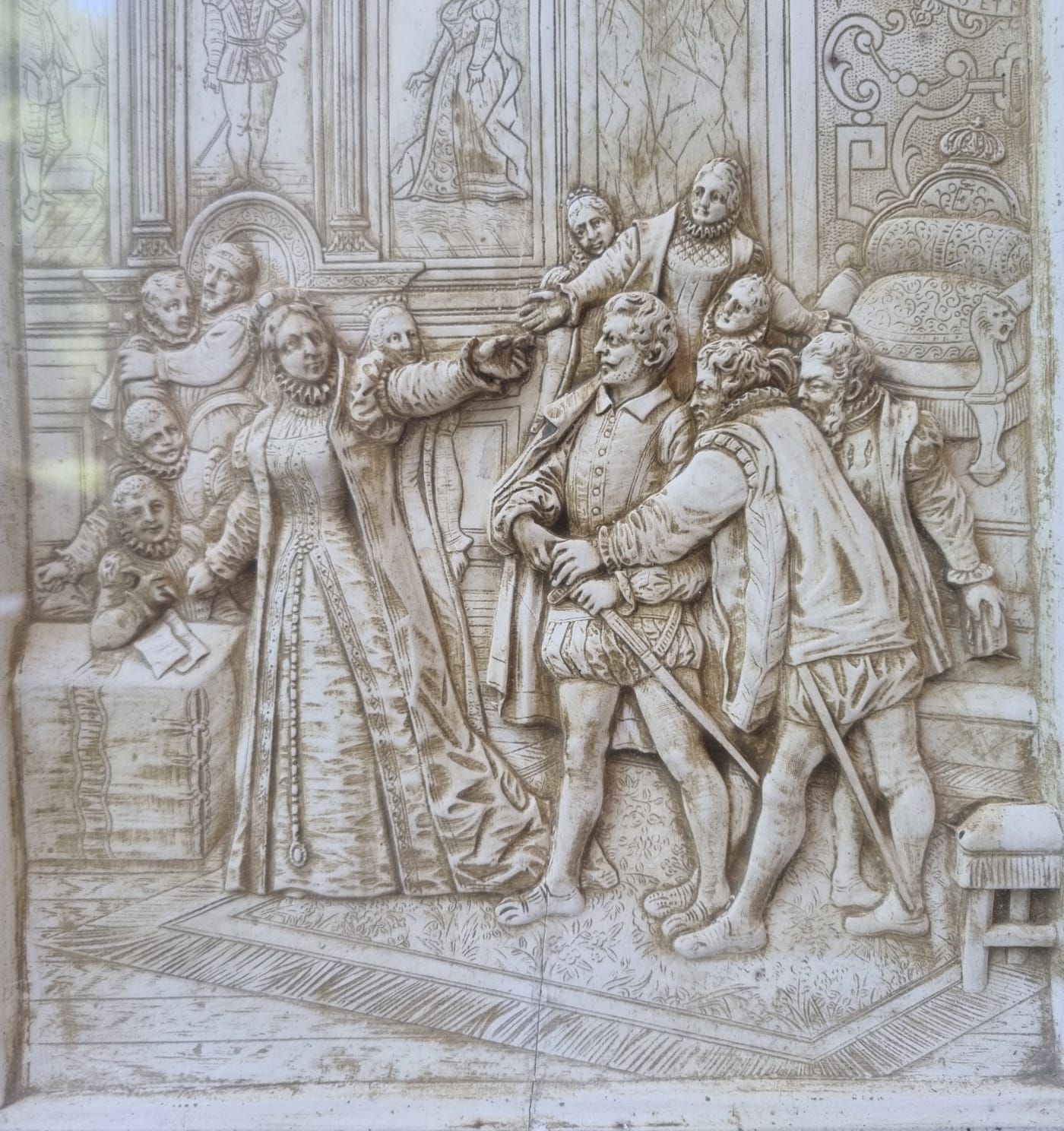

Two bas-reliefs elegantly framed have been exposed in our main room for a while. They were perking from one of the shelves, capturing the attention of everyone visiting the shop, was it for the antiques or for the wines.

At a first glance they seem carved in ivory as the surface is rather shimmery and the shadows tend to light brown tones. But upon closer inspection one can distinguish the wooden texture under a fine layer of gesso and the final coating, possibly of a glazing (oil based?) varnish.

As the featured scenes appear to be rather dramatic, with the characters seemingly performing as if they were on a stage, at a first thought they made us believe they were taken after prints illustrating theatrical plays from the 18th century. Something like the illustrations by Reinier Vinkeles or Joseph Buys, so elegant and in high demand until the beginning of the nineteenth century.

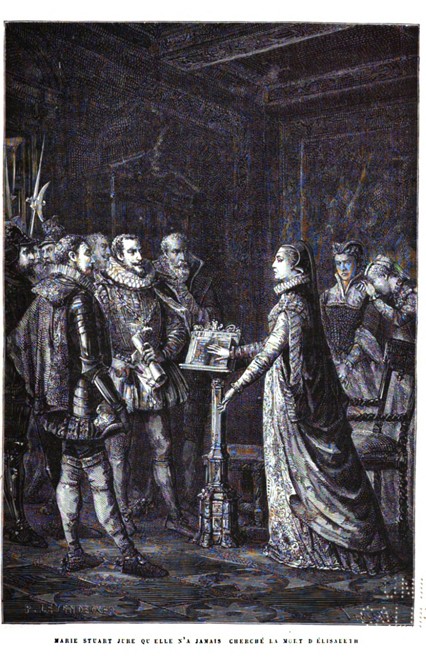

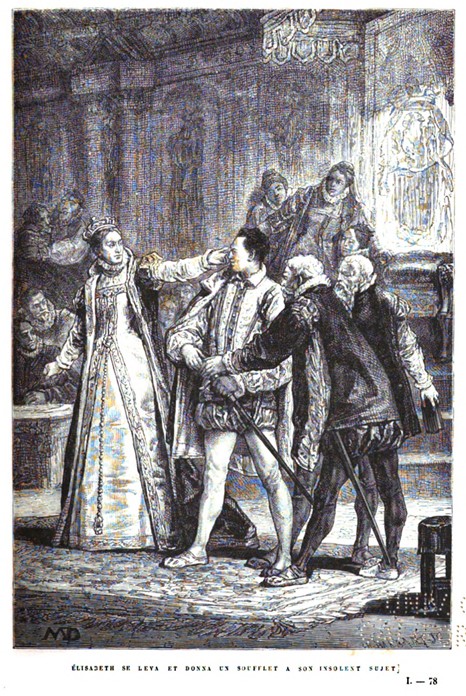

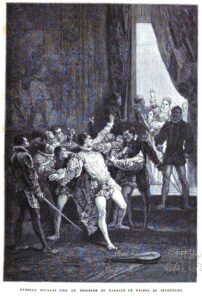

The clothing of the characters led us believe that we were looking at a staging of a play depicting the fifteenth century, but we were not sure what exactly. A solicit and attent message from a customer allowed to us to understand that we were looking at two illustrations from British History. Actually, two fairly accurate three-dimensional reproduction of illustrations from the 1877 edition of François Guizot’s (1787-1874) L’histoire d’Angleterre depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu’à l’avénement de la reine Victoria (vol. 1). These are the plate titled: Marie Stuart jure quelle n’a jamais cherché la mort d’Elisabeth on p. 605, and: Élisabeth se leva et donna un soufflet a son insolet sujet on p. 617.

The first scene sees Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots (1542-1587) on the right, rising from a seat where she has been reading, her ladies beside her in attitudes of distress, looking graciously to left towards the lords who bring her news of her impending execution, one of them holding a scroll, with fully armed guards following. As the caption of the illustration reports, Mary swore she did not conjure against Elizabeth, swearing by holding her hand on the New Testament she was reading from.

The other scene depicts Elizabeth I of England (1533-1603) striking her favorite Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex (1565-1601), when she found him guilty of treason. He was then put on trial and eventually sentenced to death.

The artist realizing the sculpted scenes copied the positions of the characters especially. The background is remarkably detailed. The characters act in highly decorated interiors, with walls covered in tapestries and painted ceilings.

The artist drafting the engravings in the book is Charles Barbant (1844-1921). Pupil of his father, Nicolas Barbant (1806-1879), with whom he associated 1863-66 (sign. Barbant et fils), Barbant was acquainted with Gustave Doré (1832-1883), who led him to color woodcuts and whose works he also cut in wood ( i.e. La Bible, 1866; Roland furieux, 1879). He worked for various magazines, including 1863-74 for “Le Monde Illustré”; “Le Journal de la Jeunesse”; 1883/84 for “English Illustrated Magazine” (G.H. Thompson, The Industries of the English Lake District); in 1889 for “Revue Illustré”. He engraved the woodcuts for: Histoire de France, 1872-79; Viollet-le-Duc’s , Histoire d’une Forteresse, 1874; Jule Verne’s, Ile Mystereuse, Michel Strogoff’s Les Indes Noires, 1874-77. According to Bénézit, Barbant was more adept at the art of engraving than his father. His works are signed with Barbant and can be distinguished from his signature by a shorter course. Works by him are in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, at the Cabinet des Estampes.

Object: PR121010